Climate Fiction between dystopia and utopia

A short conversation with climate literacy activist Dan Bloom

reported by Christiane Schulzki-Hadoutti in Bonn

KlimaSocial - from knowledge to action

Bonn, 16. 7.2019

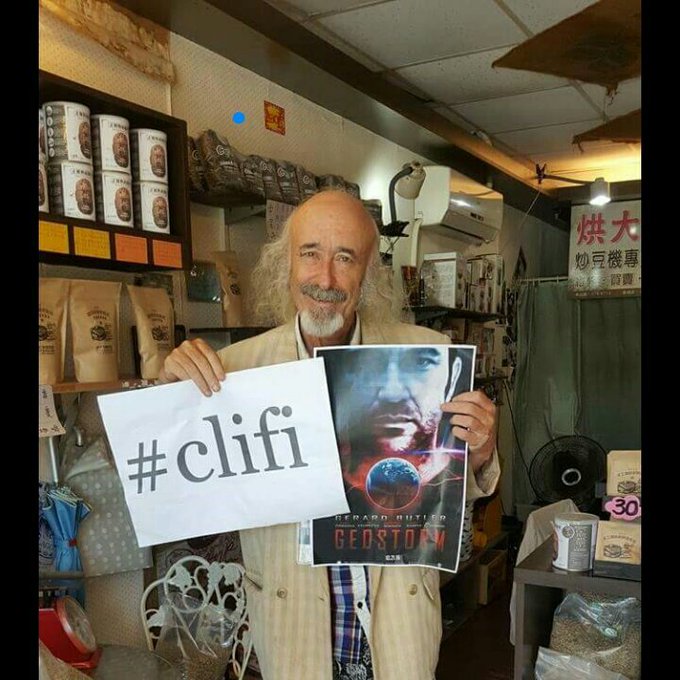

The journalist Daniel Bloom lives in Taiwan and constantly follows via Twitter, Facebook, e-mail and last but not least his blog who reports on climatic literature. He describes himself as a "literary climate activist".

When the KlimaSocial team presented eight examples of climate-fiction (cli-fi) two weeks ago, it immediately contacted them. He had read our text via Google Translate and was pleased about it. However, he did not find our report surprisingly surprising: "Among the non-English-speaking countries in Europe, Germany reports the most about climate novels on the radio and in newspaper articles."

The term Climate Fiction has only been around for a few years - and was coined by Dan Bloom. "I used the term 2011 for the first time to rouse novelists and screenwriters," says Bloom. According to Wikipedia Dan Bloom not only the definition, but also probably influenced by his numerous contacts with authors, the development of the new genre. For him, it is clear: "Just as science fiction was one of the most important literary genres in the 20th century in Europe and the US, climate novels and movies or TV series on Netflix and other channels are among the most important genres of the 21st century counting. We live cli-fi times. "He immediately tries to catch on another notation:" Perhaps we will call our century the Clifiozan. "

New concepts are for him a tool "to see things in a new way". "That's what motivates me," says Bloom. Cli Fi is now a term for novels that deal with various issues of climate change. There is no such thing as a cli-fi canon or a cli-fi agenda. For Bloom, it's actually quite simple: "Novelists go where their imagination and skill guide them in storytelling."

Dan Bloom studied French literature at the University of Boston in the 1960s, and in the 1970s he lived in Paris as a hippie. Later he worked as a newspaper reporter and editor in Alaska, Japan and Taiwan. Since 1996 he lives in Taiwan. In 2011, when he was responsible for the marketing of "Polar City Red" by US author Jim Laughter, he came up with the term "climate fiction" in order to advance the commercialization of the novel.

Bloom: "I advised Laughter to market his book as a climate-fiction thriller, which he did. Margaret Atwood, a friend of mine, also described the novel in a tweet as a climate-fiction thriller. "The tweet reached A Million's one million followers - and got the ball rolling [Q1], Meanwhile, is Cli- Fi as a genre with star authors like Michael Crichton, Margaret Atwood, Amitav Ghosh and Barbara Kingsolver become popular.

Literature dealing with climate change has been around for some time. Jules Verne imagined that the climate would change due to a shift in the Earth's axis. British author J. G. Ballard developed a world of natural disasters and climate change in various dystopian novel scenarios. In a novel from 1964, he attributes the human catastrophe to human causes: Industrial pollution is said to have disrupted the weather cycle. Various narrative strands of J. R. R. Tolkien's Ring Trilogy are now attributed to climate fiction, such as when evil sorcerer Saruman chop down tons of trees to keep his ork-operated armor machinery running. But also the setting of "Game of Thrones" on the verge of a threatening decade-long winter is added to the genre. [Q2]

Today, Dan Bloom observes two main trends in climate fiction: "Some novelists write in an apocalyptic-dystopian context. Others want their stories to be hopeful, promising and utopian. I think these will be the two most important cli-fi trends for the next 80 years. And who knows what trends will come then? "

He prefers to see the future with rose-colored glasses: "I am a born optimist and I am not afraid of the effects of global warming. I believe in the human being, who all prob

A short conversation with climate literacy activist Dan Bloom

reported by Christiane Schulzki-Hadoutti in Bonn

KlimaSocial - from knowledge to action

Bonn, 16. 7.2019

The journalist Daniel Bloom lives in Taiwan and constantly follows via Twitter, Facebook, e-mail and last but not least his blog who reports on climatic literature. He describes himself as a "literary climate activist".

When the KlimaSocial team presented eight examples of climate-fiction (cli-fi) two weeks ago, it immediately contacted them. He had read our text via Google Translate and was pleased about it. However, he did not find our report surprisingly surprising: "Among the non-English-speaking countries in Europe, Germany reports the most about climate novels on the radio and in newspaper articles."

The term Climate Fiction has only been around for a few years - and was coined by Dan Bloom. "I used the term 2011 for the first time to rouse novelists and screenwriters," says Bloom. According to Wikipedia Dan Bloom not only the definition, but also probably influenced by his numerous contacts with authors, the development of the new genre. For him, it is clear: "Just as science fiction was one of the most important literary genres in the 20th century in Europe and the US, climate novels and movies or TV series on Netflix and other channels are among the most important genres of the 21st century counting. We live cli-fi times. "He immediately tries to catch on another notation:" Perhaps we will call our century the Clifiozan. "

New concepts are for him a tool "to see things in a new way". "That's what motivates me," says Bloom. Cli Fi is now a term for novels that deal with various issues of climate change. There is no such thing as a cli-fi canon or a cli-fi agenda. For Bloom, it's actually quite simple: "Novelists go where their imagination and skill guide them in storytelling."

Dan Bloom studied French literature at the University of Boston in the 1960s, and in the 1970s he lived in Paris as a hippie. Later he worked as a newspaper reporter and editor in Alaska, Japan and Taiwan. Since 1996 he lives in Taiwan. In 2011, when he was responsible for the marketing of "Polar City Red" by US author Jim Laughter, he came up with the term "climate fiction" in order to advance the commercialization of the novel.

Bloom: "I advised Laughter to market his book as a climate-fiction thriller, which he did. Margaret Atwood, a friend of mine, also described the novel in a tweet as a climate-fiction thriller. "The tweet reached A Million's one million followers - and got the ball rolling [Q1], Meanwhile, is Cli- Fi as a genre with star authors like Michael Crichton, Margaret Atwood, Amitav Ghosh and Barbara Kingsolver become popular.

Literature dealing with climate change has been around for some time. Jules Verne imagined that the climate would change due to a shift in the Earth's axis. British author J. G. Ballard developed a world of natural disasters and climate change in various dystopian novel scenarios. In a novel from 1964, he attributes the human catastrophe to human causes: Industrial pollution is said to have disrupted the weather cycle. Various narrative strands of J. R. R. Tolkien's Ring Trilogy are now attributed to climate fiction, such as when evil sorcerer Saruman chop down tons of trees to keep his ork-operated armor machinery running. But also the setting of "Game of Thrones" on the verge of a threatening decade-long winter is added to the genre. [Q2]

Today, Dan Bloom observes two main trends in climate fiction: "Some novelists write in an apocalyptic-dystopian context. Others want their stories to be hopeful, promising and utopian. I think these will be the two most important cli-fi trends for the next 80 years. And who knows what trends will come then? "

He prefers to see the future with rose-colored glasses: "I am a born optimist and I am not afraid of the effects of global warming. I believe in the human being, who all prob

'Climate Fiction' zwischen Dystopie und Utopie

Ein kurzes Gespräch mit dem Klimaliteratur-Aktivisten Dan Bloom

reported by Christiane Schulzki-Hadoutti in BonnKlimaSocial – vom Wissen zum Handeln

Bonn, den 16. 7.2019

Der Journalist Daniel Bloom lebt in Taiwan und verfolgt über Twitter, Facebook, E-Mail und nicht zuletzt seinem Blog ständig, wer über Klimaliteratur berichtet. Er selbst bezeichnet sich als „Klima-Aktivist der literarischen Art“. Als das Team von KlimaSocial vor zwei Wochen acht Beispiele für „Climate-Fiction“ (Cli-Fi) vorstellte, meldete er sich umgehend. Er hatte unseren Text per Google Translate gelesen und freute sich darüber. Unsere Berichterstattung fand er allerdings nicht unbedingt überraschend: „Unter den nicht englisch-sprachigen Ländern in Europa wird in Deutschland am meisten über Klimaromane im Radio und in Zeitungsartikeln berichtet.“

Den Begriff Climate-Fiction gibt es erst seit wenigen Jahren – und er wurde von Dan Bloom geprägt. „Ich habe den Begriff 2011 zum ersten Mal benutzt, um Roman- und Drehbuchautoren wachzurütteln“, sagt Bloom. Wobei laut Wikipedia Dan Bloom nicht nur die Definition, sondern auch wohl über seine zahlreichen Kontakte zu Autoren die Entwicklung des neuen Genres beeinflusst hat. Für ihn steht fest: „So wie Science-Fiction zur wichtigsten Literaturgattung im 20. Jahrhundert in Europa und den USA zählte, werden Klimaromane und -Filme oder TV-Serien auf Netflix und anderen Kanälen zu den wichtigsten Genres des 21. Jahrhunderts zählen. Wir leben Cli-Fi-Zeiten.“ Unverdrossen versucht er sich gleich an einer weiteren Begriffsprägung: „Wir werden unser Jahrhundert vielleicht einmal das Clifiozän nennen.“

Neue Begriffe sind für ihn ein Hilfsmittel, „um Dinge auf eine neue Art zu sehen“. „Das ist das, was mich motiviert“, sagt Bloom. Cli-Fi sei inzwischen eine Bezeichnung für Romane, die sich mit verschiedenen Fragen des Klimawandels beschäftigen. Einen Cli-Fi-Kanon oder eine Cli-Fi-Agenda gebe es nicht. Für Bloom ist die Sache eigentlich einfach: „Romanautoren gehen dorthin, wo ihre Fantasie und ihr Geschick sie beim Geschichtenerzählen hinführen.“

Dan Bloom hat in den 1960er Jahren französische Literatur an der Universität Boston studiert, in den 1970ern lebte er in Paris als Hippie. Später arbeitete er als Zeitungsreporter und Redakteur in Alaska, Japan und Taiwan. Seit 1996 lebt er in Taiwan. Als er 2011 für das Marketing von „Polar City Red“ des US-Autors Jim Laughter zuständig war, fiel ihm der Begriff „Climate-Fiction“ ein, um die Vermarktung des Romans voranzubringen.

Bloom: „Ich riet Laughter, sein Buch als Climate-Fiction-Thriller zu vermarkten, was er dann auch getan hat. Margaret Atwood, eine Freundin von mir, bezeichnete den Roman dann in einem Tweet ebenfalls als Climate-Fiction-Thriller.“ Der Tweet erreichte Atwoods eine Million Follower – und brachte damit den Ball ins Rollen [Q1], Inzwischen ist Cli-Fi als Genre mit Star-Autoren wie Michael Crichton, Margaret Atwood, Amitav Ghosh und Barbara Kingsolver populär geworden.

Literatur, die sich mit Klimaveränderungen befasst, gibt es schon länger. Jules Verne stellte sich vor, dass sich das Klima aufgrund einer Verschiebung der Erdachse wandeln würde. Der britische Autor J. G. Ballard entwickelte in verschiedenen dystopischen Romanszenarien eine von Naturkatastrophen und Klimaveränderungen geprägte Welt. In einem Roman von 1964 schreibt er der Klimakatastrophe bereits menschliche Ursachen zu: So soll die industrielle Verschmutzung den Wetterkreislauf unterbrochen haben. Verschiedene Erzählstränge von J. R. R. Tolkiens Ring-Trilogie werden heute der Climate-Fiction zugeschrieben, etwa wenn der böse Zauberer Saruman massenweise Bäume abholzt, um seine von Orks betriebene Rüstungsmaschinerie am Laufen zu halten. Aber auch das Setting von "Game of Thrones" am Rande eines drohenden jahrzehntelangen Winters wird dem Genre dazugerechnet. [Q2]

Dan Bloom beobachtet heute zwei Haupttrends in der Climate-Fiction: „Einige Romanautoren schreiben in einem apokalyptisch-dystopischen Rahmen. Andere wollen, dass ihre Geschichten hoffnungsvoll, vielversprechend und utopisch sind. Ich denke, das werden die beiden wichtigsten Cli-Fi-Trends für die nächsten 80 Jahre sein. Und wer weiß, welche Trends dann kommen werden?“

Er selbst sieht die Zukunft lieber mit einer rosa Brille: „Ich bin ein geborener Optimist und habe keine Angst vor den Auswirkungen der globalen Erwärmung. Ich glaube an den Menschen, der alle Probleme überwinden kann, die das Schicksal aufwirft.“ Die Medien machten das Genre zu einem Genre der Weltuntergangsstimmung, „aber das war nie meine Absicht“. Er selbst hätte nie erwartet, dass Cli-Fi auch eine dystopische Seite haben werde, doch der Begriff sei offen für alle Arten von Interpretationen und Iterationen.

Die folgenden drei Cli-Fi-Romane haben Dan Bloom am meisten berührt:

· THE ROAD wurde vom Autor mit so kraftvollen Prosa-Sätzen geschrieben, dass ich nicht aufhören konnte zu lesen. Cormac McCarthy hypnotisiert den Leser mit seiner brillanten Art, Worte zusammenzusetzen. Ich erinnere mich, dass ich beim Lesen des Buches mehrmals leise geweint habe. Ich habe das ganze Buch in einer Nacht gelesen. Es gab mir das Gefühl, „dass so die Apokalypse sein könnte“. Ich hatte nie diese Art von Erfahrung beim Lesen eines Romans, nicht seitdem ich als Teenager „The Grapes of Wrath“ von John Steinbeck gelesen habe.

· FLIGHT BEHAVIOR von Barbara Kingsolver ist auch sehr gut geschrieben und ich las es langsam über einen Zeitraum von einer Woche, immer mehrere Kapitel auf einmal. Ich fühlte, dass die Geschichte sehr gut die Probleme erklärt, die Klimaaktivisten und -verweigerer haben, wenn sie versuchen zu kommunizieren (und dabei normalerweise scheitern). Der Roman ist eine Fabel, mit Mystik und übernatürlichen Ereignissen. (Siehe hier auch die Rezension von KlimaSocial)

· EISTAU von Ilija Trojanow, das ich 2018 in englischer Übersetzung las, erinnerte mich an SOLAR von Ian McEwan. Es ist eine Satire darüber, wie die Reichen teure Tickets kaufen, um wie Touristen auf Kreuzfahrtschiffen das Ende der Welt zu besuchen. Die Satire machte EisTau nervös und avantgardistisch.

Auf Dan Blooms Leseliste stehen nun Cli-Fi-Romane wie „Aqua“ von Jean-Marc Ligny und „Somewhere Out There“ vom italienischen Schriftsteller Bruno Arpaia.

Quellen:

[Q1]: Der Tweet ist leider nicht mehr auffindbar.

[Q2]: Marc DiPaolo: Fire and Snow: Climate Fiction from the Inklings to Game of Thrones", https://www.sunypress.edu/p-6585-fire-and-snow.aspx

Tipps: